Threats to Majority EV Adoption, and How Not to Be One

“You can’t really know where you’re going until you know where you’ve been.” Insightful words of wisdom from poet Maya Angelou. The transportation electrification industry talks a lot about where we’re going, we’ve all heard the stated goals by 2030 or 2035.

And many of us have been at this long enough to understand where we’ve been. In our case, as with any technology revolution, it’s also really important to know where we are on the journey. Because the things that got us to this point may not be the ones that get us where we’re hoping to go. Understanding where we are is critical to making sure that each of us is part of the solution – not part of the problem – to achieving majority EV adoption.

Where Are We on The Journey?

I have a slightly different metric that I prefer for tracking “where we are.” Because the aim of electrifying transportation is emissions reduction, when we throw percentages around, we should remember that emissions will come down in proportion to the percentage of ALL registered vehicles (technically, the percentage of ALL vehicle miles traveled) that are electric. So, while annual % of new car sales – the US EV Adoption Rate (EVAR) – is a great trend to watch, we should really stick to talking about the % of all registered vehicles that are EVs – the US EV Penetration Rate (EVPR). Currently in the US, this is around 1.3%. Even if new car sales reach the high end of the EPA targets in the table above, the percentage of all registered vehicles which are EVs – the US EVPR – would only rise to between 10-12% by 2032. It would be one heck of a start, but a long way from majority adoption.

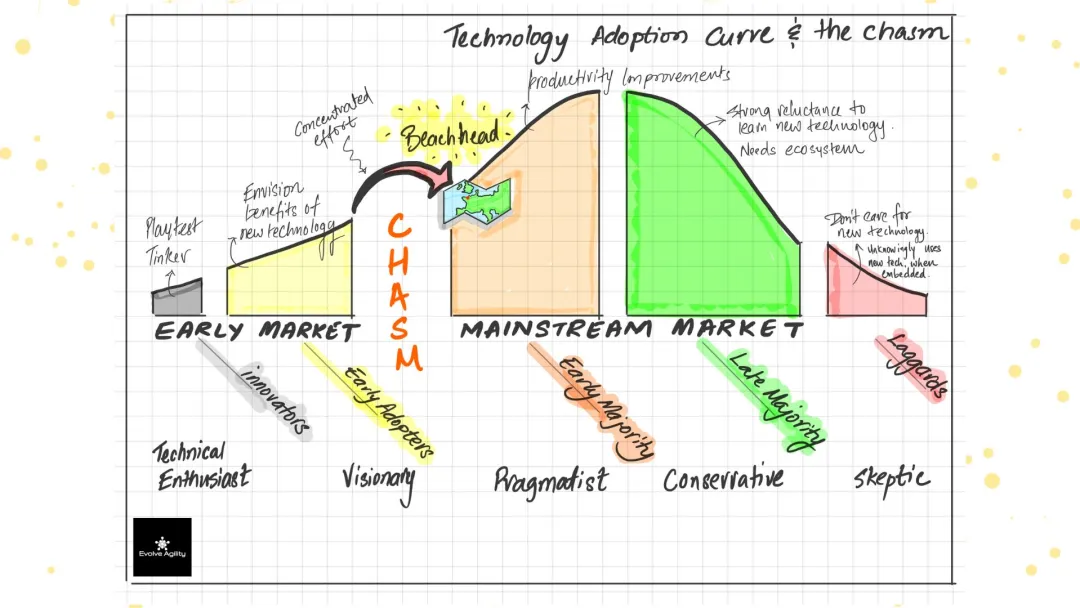

So if we are short of majority adoption, does this mean that we continue to rely on innovators and early adopters to drive these new EV sales, to carry us up the S-curve? I think that as an industry, we are unfortunately acting that way, but I would argue that the innovators are gone and we’re running out of early adopters. It’s time to turn our focus toward what is demanded by early majority adopters, and as with any new technology, this evolution is not a passive one for the industry. It’s a call to action for those of us developing products and services in the space – a call for innovation of business models.

Crossing the EV Adoption Chasm

The principal of Crossing the Chasm tells us that everything that has gotten us to 1% EV adoption in the US, has little to do with what will get us from 1% to 10%, let alone majority adoption. So, if we are to drive significant YOY increases in sales over the next five years, and we have yet to make the necessary adjustments to business models and education, then we’re behind. This is my opinion, but better to think you’re behind and be wrong, than to think you’re doing just fine and be wrong.

Here is a list of things that early adopters have been willing to play along with, that will be increasingly less likely to fly with the people who might adopt EVs over the next five years and beyond:

Business Models that Build a Bridge

A good example of an early business model that has begun to give way is the Tesla supercharger network. Along with their strategy to start at the very top end of the price range, Tesla’s early EV sales included lifetime electricity pre-purchase. These funds were used to build out a DCFC network – and they built one fantastic DCFC network. On their march to nearly 70% EV market share, taking ownership of this project in exchange for more car sales made a lot of sense. But as all EV makers’ price points drop, along with Tesla’s market share, it’s no wonder they are backing off commitments to expand the network. Like the $100k EV sedan, the Tesla DCFC network served its purpose in getting us to 1% EV adoption in the US. But just as we’ve run out of target consumers for those luxury sedans, so shall we run out of eager users of slow public chargers that take them out of their way.

We need to start thinking about how we sell EVs to Americans who live in rental apartments, to single parents working two jobs, and eventually, to people whose politics tell them that EVs are a government conspiracy. Now is the time to focus on what majority adopters might value in an EV. As we move from early adopters to majority adopters, and consumer demands for EVs shift, here are a few examples of business models that are responding:

Cost-effectiveness is king. Majority adopters will select EVs based on their having a lower total cost of ownership than their ICE counterparts. Auto OEMs, with the notable exception of Tesla, seem committed to producing EVs at increasingly more affordable price points. Ford CEO Jim Farley said earlier this summer, “We have to start to get back in love with smaller vehicles. It’s super important for our society and for EV adoption.” Electric utilities like Florida Power & Light and Duke Energy are providing homeowners with EV charging rates as low as free for off-peak electricity.

Convenience is a must. The perception that charging an EV is far less convenient than filling up an ICE vehicle’s gas tank, is a major hurdle for majority adopters. It’s also true, based on the charging patterns we’ve allowed ourselves to accept because early adopters tolerated it. We need to explain to potential EV owners that they are able to charge their EV at home like their iPhone, that it’s easier than stopping to pump gas. Companies like 3V Infrastructure and SWTCH are focusing on providing charging-as-a-service (CaaS) for multifamily buildings, where early adoption has necessarily meant highly inconvenient charging.

Reliability and Ease-of-Use. Research shows that those resisting the jump to EVs are of the opinion that EVs and EV chargers are both unreliable and difficult to use. Again, these concerns are fairly well founded, and EV sales have plowed forward in spite of them based on the high tolerance of early adopters for trying out new things. The good news is that at-home charging, longer range batteries and education efforts are already moving to improve these areas. Many utilities will install a home charger cheaply for single-family homes; average EV range is around 300 miles, up from just over 200 miles only 5 years earlier, and more than double what it was a decade ago; and groups like Forth Mobility are designing and implementing affordable EV carsharing programs, engaging in community-centered outreach and education, and developing tools to reduce barriers for EV adoption

Conclusion

There are enough external threats focused on preventing EVs from realizing their full potential. It’s important that those of us working to advance the market are honest with ourselves about where we are, and about what it will take to get where we’re going. We are very early on the technology S-curve, which means we’re standing on a steep slope. The risk of back-sliding is real, and unless we are able to build bridges across the chasm with our business models, those who would like to see the US miss its targets for EV adoption just may get their wish.

Stay tuned, next Blog in this series…..“EV Charging – Industry Focus vs What EV Owners Need”

Recent Posts

Examining EV Adoption at the State Level

While we’ve made progress in growing EV adoption over the last several years, the bulk of this progress has come in a relatively...

What is the Purpose of the EV Charging Industry?

In part two of this blog series, we discussed the disproportionate focus of the EV Charging Industry (EVCI) on DCFC, even though it...

EV Charging – Industry Focus vs What EV Owners Need

An essential ingredient in the transition to electric vehicles is forgetting what we’ve learned about cars altogether. For example, we’ll need to forget...