In part two of this blog series, we discussed the disproportionate focus of the EV Charging Industry (EVCI) on DCFC, even though it is Level 2 and Level 1 charging that will satisfy the majority of all EV fueling needs. It is also Level 2 and Level 1 charging that have the capability to deliver on the demands of majority adopters – that their charging be reliable, convenient, easy and cheap.

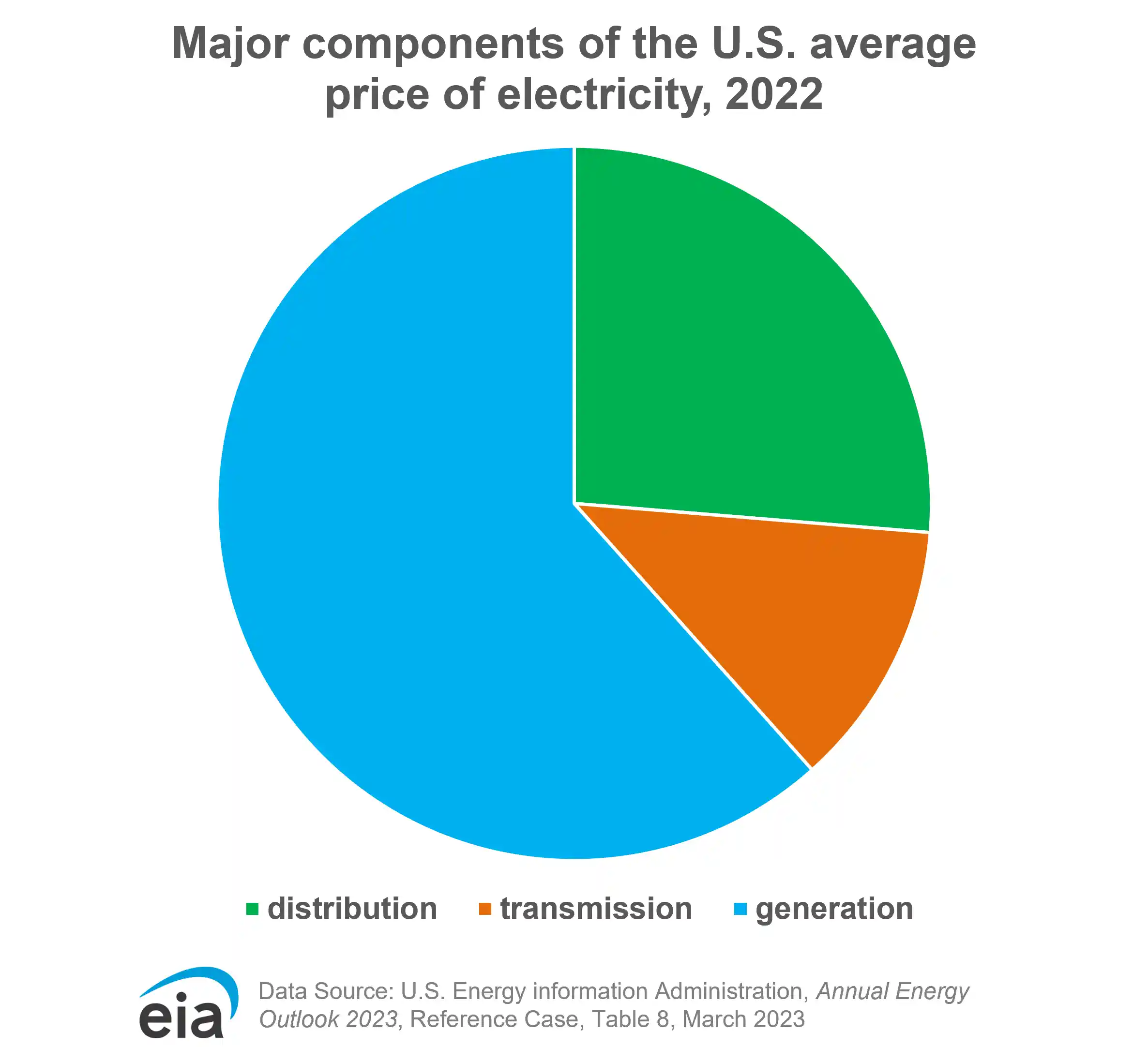

And focusing on Level 2 and Level 1 at-home and workplace charging is cost-effective and minimizes grid investment, protecting an important EV advantage by not contributing to an increase in electricity rates.

Still don’t believe me that what majority EV adopters want is cheap, convenient and reliable home charging? That they’re not interested in cool, super-fast charging depots, with great lattes where you can chat with other EV drivers? Don’t take it from me, listen to what this guy thinks:

“Ford believes it will take more than jumbo rebates to truly break through with the estimated 19 million people in the U.S. interested in electric vehicles. It will take – you guessed it – convenience, peace of mind, and expert service. It will take a modern-day version of the friendly filling station, only this time you “fill ’er up” at home.”

Electric Vehicle Industry vs. the EV Charging Industry (EVCI)

Are the electric vehicle industry and the EV charging industry (EVCI) the same thing? If not, do they at least share the same purpose? Having a purpose is important in any organization, but what is most important is the common understanding of this purpose by the people in the organization. I’m not at all convinced that those of us working in the EVCI have this common understanding, and I am certain that the way we are behaving reflects as much.

The purpose of the electric vehicle industry is pretty straightforward – the electrification of transportation. Which makes the scorecard process very simple. There is a single metric of success – the US EV penetration rate (EVPR), the % of all registered vehicles that are electric. Importantly, this metric aligns with nearly all EV policy in the US – from federal targets, to federal and state tax credits, to carbon offset mechanisms. All of these policies are designed to replace vehicle miles driven in ICE vehicles, with miles driven in electric vehicles, and reap the associated emissions reduction. Pretty straight forward, and there are people working across the EV ecosystem who anxiously await the quarterly and annual results of EV sales to track their progress with this metric. Success or failure is easy to measure.

The EVCI was born to facilitate the electric vehicle industry’s growth, “if you build it, they will come” we were told. Whether or not that statement is true has been the subject of great debate, and it certainly seems dependent on what, specifically, we build. But what should concern all of us is the lack of connectivity between the “building” and the “coming” – between the charging put in place and the EVs that might use it. It seems that in spite of its original intent, the EVCI has developed a life of its own, and scorecard metrics to go along with it. An entirely separate set of metrics whose quarterly and annual release tells us how many chargers or charge ports have been added, how many we now have, or worse, how much money we’ve spent on them.

The difference between the purpose of driving EV adoption, versus the purpose of installing EV charging, is stark. In the case of the former, your main objective would be to install as little EV charging infrastructure as possible to deliver a given EV adoption rate; and in the latter your main objective would be to install as much EV charging infrastructure as possible, regardless of its effect on EV adoption rates. That’s a big difference.

Incentivizing CPO Behavior

The EVCI, for its part, pushes back on this notion that EV chargers are being installed and the charge point operators (CPOs) who own them don’t care about utilization. And its true that utilization is determinate in whether or not an investment in an EV charger has an acceptable rate of return. But many investments being made in public charging are heavily subsidized by federal grants and utility rebates. The remaining portion of the investment is often made by a CPO or site host with a non-charging revenue business model – where charging EVs is a desired amenity, but at best is a means to an end, and at worst a loss leader.

If the government and utilities have approval to spend taxpayer and ratepayer funds with the objective of driving higher EV adoption, then they have a responsibility to design programs which tie the spending to this objective. Funds that are used to subsidize the installation of expensive charging stations that may or may not be utilized, will necessarily drive up electricity rates. In the case of public DCFC, this stranded cost is compounded because utilities will spend significantly more on the grid side, on top of the rebates. If such funds are being spent in the interest of advancing a private corporation’s non-EV charging business model, then we’ve really lost site of the objective of driving higher EV adoption.

There is a better way – and its simple. Performance-based energy efficiency (EE) programs – run by these same utilities – pay only when the objective of the programs is met. In the case of EE, utilities will pay a certain “cents per kWh” rate for delivered and verified energy efficiency. With EV charging this is much easier because the charger itself is a sub-meter. The carbon reduction programs in Western states have demonstrated this approach and shown the potential for performance-based EV charging infrastructure rebate programs. More on this in part four of this blog series, “Policy Fixes – EV Charging Programs 2.0”,coming soon.

The Hidden Cost of DCFC Overdevelopment- Lower EV Fuel Savings

Instead, the investment decisions that we make collectively – government, utilities, private sector – should as a first order, attempt to leverage investments already made in the electric power grid. Where capacity exists, it should be tapped into, and we should right-speed our charging to fit the times of day that power is most available and cleanest. Luckily, if we take this approach, much of the distribution infrastructure required to add EV charging has already been built out, in a system that has very low capacity utilization.

Think of how you, and every EV owner, assessed their own personal investment in home charging – as a microcosm of the EVCI business. You found an available circuit, or invested minimally at the panel as necessary, found the shortest power run to a charger location, installed the cheapest reliable charger, unless Level 1 power was adequate. Why should we think differently when we invest taxpayer and ratepayer money than we do when it’s our own money?

What’s more, the availability of grid capacity and power currently aligns well with the times and places that are most convenient for EV users, and 300+ mile batteries give more flexibility than ever to make it back to “home base” without needing a charge. Of course EVs will upset this balance as they become more prevalent, and managed charging approaches will need to shift accordingly. But batteries on the grid are already demonstrating their value, and by the time that EVs become a relevant grid load, V2G will likely allow us to see these batteries-on-wheels as a grid resource.

It would be great to see the EV charging industry (EVCI) get behind this approach to sensible, cost-effective charging infrastructure that is aligned with EV adoption rate increases. But there is no reason to believe that this will happen until policies are put in place that discourage the profitable business of building out (potentially) stranded infrastructure assets and charging-as-a-hook installations in support of other business models.

We’ve Been Here Before

For the handful of us in the EVCI who come from the energy efficiency (EE) industry, this lack of alignment within the clean energy space seems all too familiar. It wasn’t much more than a decade ago, that the renewable power industry became the very well-funded darling of clean energy. Those of us who had toiled for many years working for regulation and legislation to advance energy efficiency welcomed the renewable folks and their iconic (sexy?) solutions with open arms.

But it quickly became clear that not everyone in the renewable power business was aligned with our long-standing purpose of climate change mitigation and resource conservation. In fact, some had no interest in advancing EE, which they saw as cutting into the load that they would be required to serve. They wanted to build renewable power plants to generate the electricity that people waste.

The renewable power industry was happy to have us sign on to their Renewable Portfolio Standard, which we did enthusiastically, because it aligned with our purpose. But when it came time for them to reciprocate, and sign on to an Energy Efficiency Portfolio Standard, we were met with resistance by some. And why not, such a standard would work against their purpose which was to install as much renewable generation as they could, not to mitigate climate change. The EE and renewables industries eventually found a great deal of alignment and the resulting policy successes benefitted clean energy broadly. Here’s to hoping that the electric vehicle industry and the EVCI can unite around the common purpose of advancing transportation electrification.

Stay tuned, next Blog in this series…..Part Four – “Policy Fixes – EV Charging Programs 2.0”

Recent Posts

Examining EV Adoption at the State Level

While we’ve made progress in growing EV adoption over the last several years, the bulk of this progress has come in a relatively...

What is the Purpose of the EV Charging Industry?

In part two of this blog series, we discussed the disproportionate focus of the EV Charging Industry (EVCI) on DCFC, even though it...

EV Charging – Industry Focus vs What EV Owners Need

An essential ingredient in the transition to electric vehicles is forgetting what we’ve learned about cars altogether. For example, we’ll need to forget...